Danish Engineer Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor

A biography by

N.J. Bordier-Skougor

Table of Contents

III. Hjalmar's Contentious Debut in New York

IV. Hjalmar's Blueprint for Nueva Rosita, Mexico

V. Hjalmar's Role in Guggenheim's Project in Atacama, Antofagastino Province, Chile

Vl. Hjalmar's Role in Alcoa's Project in Arvida, Quebec Province, Canada

VII. Hjalmar's US-Mexico-Chile-Canada Connection

In writing this biography of my Danish grandfather, Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor, my purpose is three fold.

First, I want to provide a character portrayal of his adventurous and heroic personality based on family recollections and inferences from external sources, including the egalitarian thrust of his goals.

Second, I want to describe and summarize Hjalmar's professional roles and accomplishments in four different cities and countries in North and South America: New York in the US: Nueva Rosita in Mexico; Saguenay in Quebec Province in Canada; and Antofagastino Province in Chile.

My description will compare and contrast what transpired and their consequences, emphasizing the differing political contexts in which they occurred. It will address the enigma of why Hjalmar's ideal Nueva Vista blueprint and its multifaceted goals are reflected and enhanced in in Alcoa's project in Canada's Quebec Province, but largely overlooked by the Guggenheim project in Chile's Antofagastino Province.

The visibly egalitarian goals of Skougor's blueprint in Quebec, drawn up in partnership with Columbia University architect, Harry Beadslee Brainerd, were viewed as aiming to create a "socio-industrial utopia", in combination with a panoply of influences. But the impact of the blueprint appears to have been significantly diluted in Chile, via actions appearing to reinforce existing socio-political-economic stratification.

Third, my purpose is to encourage others to author and publish portrayals of family members' lives, especially those whom they admired and who influenced their lives. In my case, my grandfather's values and visions undoubtedly influenced mine, especially their egalitarian thrust. They encouraged me to pursue similar goals more single-mindedly than I might have otherwise.

One common thread within our family reflects our attachment to the egalitarian thrust of key aspects of the Danish culture. It is reflected in several generations of our family's devotion to the works of renowned Danish storyteller, Hans Christian Andersen, per the following:

"Andersen's fairy tales, consisting of 156 stories across nine volumes,[1] have been translated into more than 125 languages.[2] They have become embedded in Western collective consciousness, accessible to children as well as presenting lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity "

When I was in grammar school and an avid reader, my father -- Hjalmar's son and only child -- gave me an illustrated book of Andersen's tales. Frankly, what I read frightened and saddened me, especially the tragic tale of the Little Match Girl. At such a young age, I had never before read about such extreme poverty that a little girl was sent out into the street alone to sell matches to help her family survive. That she died doing so was emotionally overwhelming.

I'm pretty sure that such widely read stories convinced Danish readers that much more had to be done to prevent such dire straits from costing a little girl her life. I am quite sure, reflecting on the life and values of my Danish grandfather Hjalmar Skougor, that the egalitarian principles reflected in his professional work is likely to stem from core premises of the Danish culture.

lll. Hjalmar's Contentious Debut in New York

After Hjalmar arrived in New York, he recommended, planned, and implemented projects in four countries in North and South America:

United States: New York and New Jersey

Mexico: City of Rosita

Chile: Antigasto Province, Atacama Desert

Canada: Quebec Province, Saguenay.

From 1913 to 1920, Hjalmar was engaged by the Guggenheim Brothers, Chile Exploration Co. and Braden Cooper Co., as designing engineer for the Chile Atacama Desert project. He continued to work for the firm after this date, but took on other projects.

In 1918, he boldly proposed constructing a moving sidewalk between Times Square and Grand Central Station, to replace the underground subway. (New York Times Sidewalk Shuttle May Get a Tryout.)

"Asked yesterday to comment on t7e statement of Hjalmar E. Skougor, a designing engineer, printed in THE TIMES on Friday, that a moving plat- form would better serve the public than the present shuttle service through Forty-second Street between Times Square and the Grand Central Station, Public Service Commissioner Whitney replied:

"Some time ago I stated, and now emphasize, that the two tracks on the north side of Forty-second Street present the possibility for the development of a moving platform. If the men inter- ested in the development can submit plans and demonstrate the practicability of such a installation, I am sure the commission will be very open-minded on the adoption of such a method of transportation between the two points.' In certain respects the moving platform method presents advantages over the train method, particularly in short stretches where intense traveling prevails. Incidentally, a moving platform, if it can be proved practicable, would present the opportunity for access from any of the properties on the street."

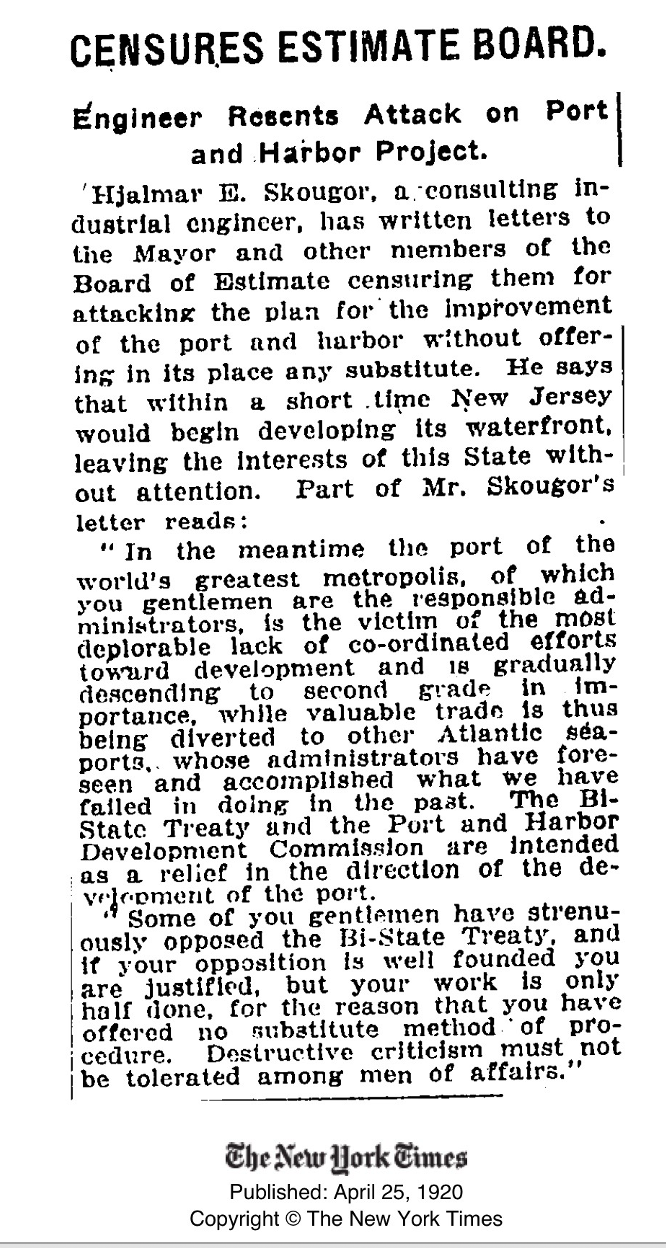

In 1919 in another bold proposal, Hjalmar devised a strategy and plan for developing the shipping port network on both sides of the Hudson River abutting New York and New Jersey -- while criticizing officials for failing to do so.(See

Censures Estimate Board: Engineer resents attack.

New York Times, April 25, 1920.)

When I first read New York Times articles describing my grandfather's outspoken views and criticisms of high-level New York officials, I was somewhat taken aback. In 1921, he submitted an application to patent an engineering invention, and was granted the patent by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) in 2024. In his application, he stated he was a "subject of the Kingdom of Denmark"! Obviously he was undaunted by citizenship in another country when applying for US patent rights.

This verve was exemplified when he took to task the Mayor of New York and Board of Estimate officials, in an open letter, for failing to devise a workable and competitive plan to develop New York ports around Manhattan and along the Hudson River!

Hjalmar's personal verve appears to have been a core component of his character, and one of the primary motivations driving his unusual engineering goals and accomplishments, even while working for multinational corporations in inhospitable and even barren lands, such as the Atacama Desert in Chile.

He was also keenly interested in new technologies. In 1921, at a meeting of engineering associations on heat, light, and power options for New York, Hjalmar described possibilities for generating electricity from tides . . . and proposed eliminating the use of gas for lighting.

IV. Hjalmar's Blueprint for Nueva Rosita, Mexico

Hjalmar designed and published a development plan for Nueva Rosita entitled, Mexico, a Carefully Planned City: Pleasing. Confortable and Hygienic. (See Coal Age, Vol. 19, No. 22 (June 2, 1921): 983–987, and Coal Age, Vol. 19, No. 23 (June 9, 1921), 1037–1040.)

Hjalmar included in his plan his observations of current conditions; extensive drawings of proposed building architectures and layout of public/private spaces; and numerous recommended improvements. They include the following:

- "Native miners and laborers in Mexico today as a class are unaccustomed to comforts and hygienic conditions of any kind. This is evidenced by the conditions under which they now live. It is therefore considered a distinct and novel procedure to afford them the comforts which had been planned."

- The plan will "provide Mexican miners and laborers with conveniences, accommodations, and considerations commensurate with such improvements as are adopted by similar industries in the United States."

- "The plan. . . will compare favorably . . . in the way of labor-saving and safety devices tending to foster the health and well-being of the workmen."

- "A system of sanitary sewer mains is provided throughout the town site. The sewage from this system together with that from the plant is treated in a sewage disposal plant, the purified water from which can be used for agricultural purposes."

- "The following public buildings have also been provided: a community building, stores, theatre, club, public market, public school, a hospital, and church."

- "A Mexican laborers house of ample proportions will be provided. It will be so arranged that each room has air and light.""

- "Native Mechanics Houses. The houses are in all cases of the duplex type, with three rooms, a kitchen, and porch."

- "To eliminate the monotony in appearance which would be inevitable if all houses were of one design, three distinct types will be provided for this class of workmen."

- "For the education of the children of this community. . . a public school has been provided."

- "A large community farm will be provided in which every man who so desires will have a plot. "

Hjalmar's proposal is considered as one of his best known works, which is cited by architects and scholars of industrial cities. Hjalmar used this city as a model for the design of buildings he co-engineered in Chile.

In the chapters below, I address the apparent enigma of why key aspects of Hjalmar's original idea design of Nueva Rosita were adopted and even enhanced in subsequent applications, while others were overlooked. I also explore causes and consequences of differential applications, and their significance and relevance today.

V. Hjalmar's Role in Guggenheim's Project in Atacama, Antofagastino Province, Chile

Hjalmar was a key player in designing a sequence of varying iterations of Guggenheim's Project in Chile. While his Nueva Rosita blueprint significantly influenced these iterations, their implementation diverged and often contradicted his goals, e.g. with respect to the egalitarian thrust of his professional goals.

Reviews of his plans differ in the degrees to which they lauded his work or criticized it. One example of negative evaluations can be found in the following:

Damir Galaz-Mandakovic and Francisco Rivera. Revolution and Resistance in the Desert: The Guggenheim System's Impact on Nitrate Mining and Society in Atacama, 1926–31. Johns Hopkins University Press. Volume 65, Number 2, April 2024.

"In 1926, during an economic crisis that severely impacted the mining industry, Guggenheim Brothers, the Guggenheim family business, implemented a new technological system to extract saltpeter from the Atacama Desert in northern Chile. Known as the Guggenheim system, this cutting-edge technological innovation had a significant impact on regional society and facilitated the introduction of Chilean saltpeter into the global fertilizer market.""

"For this system to succeed, however, it had to incorporate a sociopolitical strategy based on a highly hierarchical and well-controlled labor force. Through their political and cultural influence in the region, the Guggenheim family's industry transformed a remote area into a state periphery, creating new ways of inhabiting the desert within a strict framework in which workers' lives were regulated by company-imposed labor discipline. With more political power than the state, the Guggenheim family sought to suppress any social agency deemed dangerous to the production of saltpeter."

"Pampinos and the Chilean Labour Movement"

"Mine-workers and their families had to confront difficult living and working conditions in the Pampa. Along with their exposure to the harsh desert weather, they had to face poverty, long working hours, an unequal relation to more senior employees, and a salary paid in tokens. Their fight for a better quality of life and greater social justice motivated the birth of saltpetre workers’ unions. Together with other emerging unions that were rising across the country during the first decades of the 20th century, they advanced pioneering social demands that played a fundamental role in the institution of Chile’s first labour laws . . . .which brought about an enduring social and political transformation."

Similar critiques can be found in the Google Arts and Culture/UNESCO World Heritage appraisal entitled Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works, Chile: Rescuing heritage on the Chilean Pampas.

It includes the following:

"These mining towns were home for more than eight decades to thousands of people, who worked extracting and processing nitrate, and forged a distinctive pampino culture. This land, characterised by a hostile environment and one of the driest deserts in the world, became a source of great prosperity to the country. It echoes the struggle of miners and their families for better living conditions, which gave birth to the Chilean labour movement."

"The isolation of Humberstone and Santa Laura, located far away from main cities, made it necessary for the companies to provide food, water and other elements to the mine-workers and their families."

"Moreover, because annual rainfall is next to nil, it is impossible to grow anything. In this hostile environment, miners and their families coming from Peru, Bolivia and Chile lived and worked in company-towns for decades, processing the largest deposit of this mineral in the whole world and forging a distinctive culture. Men always predominated and women of all ages were scarce. The majority of them were country folk who had decided to emigrate because of the poor conditions reigning on Chilean farms and estates. The workers of Bolivian and Peruvian origin, on the other hand, generally came from the Andean valleys."

"Miners did not receive money for their job, as their salary consisted of tokens that were handled periodically. Made of metal or plastic, they were delivered by the offices and could only be used at the general store in exchange for a variety of products. This allowed the store owners to fix higher prices compared to other towns. It also made it extremely difficult for workers to return to their native lands."

A thoroughly researched perspective and more complimentary evaluation is provided by the noted Chilean geologist, Patricio Espejo-Leupin. He is an expert in the history of the Atacama Desert, including the efforts of the Guggenheim Brothers to implement a new technological system to extract saltpeter from the desert. He published a lengthy book on the subject in 2021 which describe my grandfather's role. It is entitled

Edgar Stanley Freed, los Guggenheim y la industria del salitre. Pampa Negra Ed. 2021 entitled:

Translation: Edgar Stanley Freed, the Guggenheims and the saltpeter industry

In 2025, Espejo-Leupin also wrote and published an in-depth analysis of Hjalmar's role, entitled

The Danish Engineer Hjalmar Skougor and the 'Maria Elena' Nitrate Work.

The author wrote the following about Skougor's role:

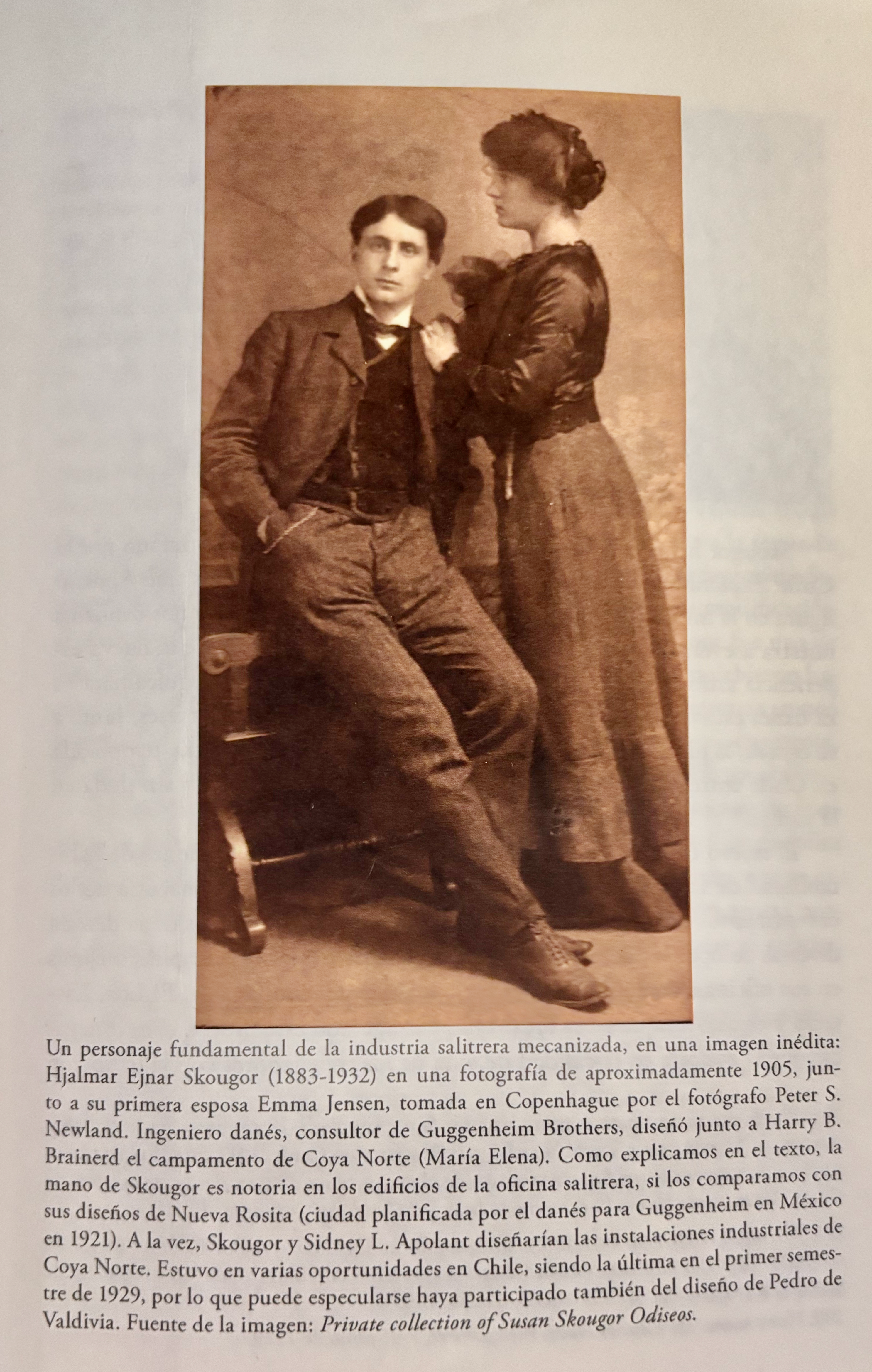

"This article analyzes the little-known but significant role of the engineer Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor in the history of the nitrate industry through the design of the plant and company town of the first nitrate work that used the so-called "Guggenheim system", proyect originally called Canada, then Coya Norte and finally María Elena. That method meant one of the greatest innovations in the nitrate business in the twentieth century. Along with his biography, we examine the case of María Elena and one of his previous commissions: Nueva Rosita in Mexico, whose design we propose inspired part of his first nitrate project. Due to his participation in the planning of the copper plants of Chuquicamata and El Teniente, and the second mechanized nitrate work, Pedro de Valdivia, we highlight Skougor as one of the engineers with the greatest impact in large-scale mining in Chile in the first half of the twentieth century."

"The case of Hjalmar Skougor is a good example of the migration of technically educated people from Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, while the United States was experiencing economic and political expansion into the rest of the Americas, especially in search of vast natural resources in underdeveloped countries. As we have explained, the role that Skougor played in planning the projects that would later become known as the great copper mining operations of Chuquicamata and El Teniente, placed him as one of the most important engineering figures in the development of these sites, which have played a significant role for Chile not only economically, but also culturally and as a symbol of identity."

"It's surprising to see how, among the thousands of pages written about the history of Chuquicamata, Sewell, and Caletones, no mention has been made, until now, of the role played by Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor in the design of their facilities, both industrial and residential. In the case of María Elena, historiography and architecture recorded his name alongside that of Harry Brainerd, but without being able to say anything more about his life."

"This work, we believe, corrects this absurdity. It is important for the current pampas community, the last one, to learn about the life of one of the creators of its nitrate works. The design of the plant, the camp, the buildings, in short, the spaces where daily life took place, determined much of the identity of its inhabitants. One of the elements that may seem striking is the fact that we find an engineer dedicated to architectural and urban design, immersed in the details of different types of housing and buildings."

To set the stage for Chapter VI describing Hjalmer's role in Alcoa's Project in Arvida, Quebec Province, the following observation concerning shortcomings of the Maria Elena effort are provided by University of Texas scholar Felipe Correa. His analysis points to the need to authentically recapture Hjalmar's pioneering work in Nueva Rosita and the Atacama Desert, especially its egalitarian thrust, and afford him the opportunity to extend and amplify it in the more encouraging and welcoming environment in Canada :

Felipe Correa. Beyond the City: Resource Extraction Urbanism in South America 9781477310243. University of Texas Press, 2016.

"While María Elena provided an overall improvement in quality of life to the pampino. the provision of housing was the complex’s greatest shortcoming, where the differences among social groups were most noticeable."

"The town plan was drafted in early 1924 by the architect Harry Beardslee Brainerd (1887–1977) in collaboration with the engineer Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor (1884–1932) as part of an architectural partnership that would continue after María Elena to become responsible for important town plans, including one for the Canadian company town of Arvida, Quebec, for the Alcoa Aluminum Company."

Vl. Hjalmar's Role in Alcoa's Project in Arvida, Quebec Province, Canada

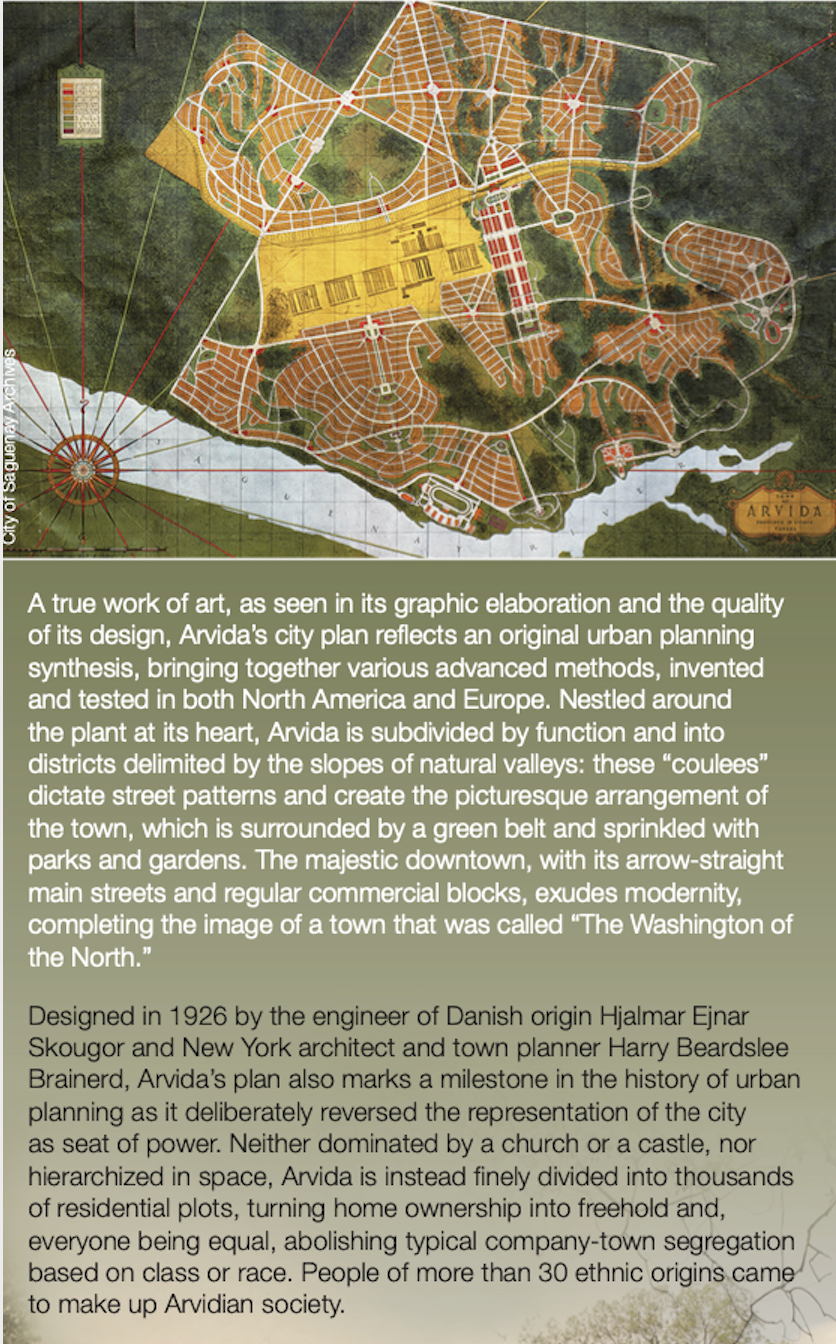

The government of Canada has honored the accomplishments achieved in Arvida nearly a century ago, through the efforts of a large team of intrepid builders led by the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). In the following declaration, my grandfather is included among them: Arvida National Historic Site of Canada.

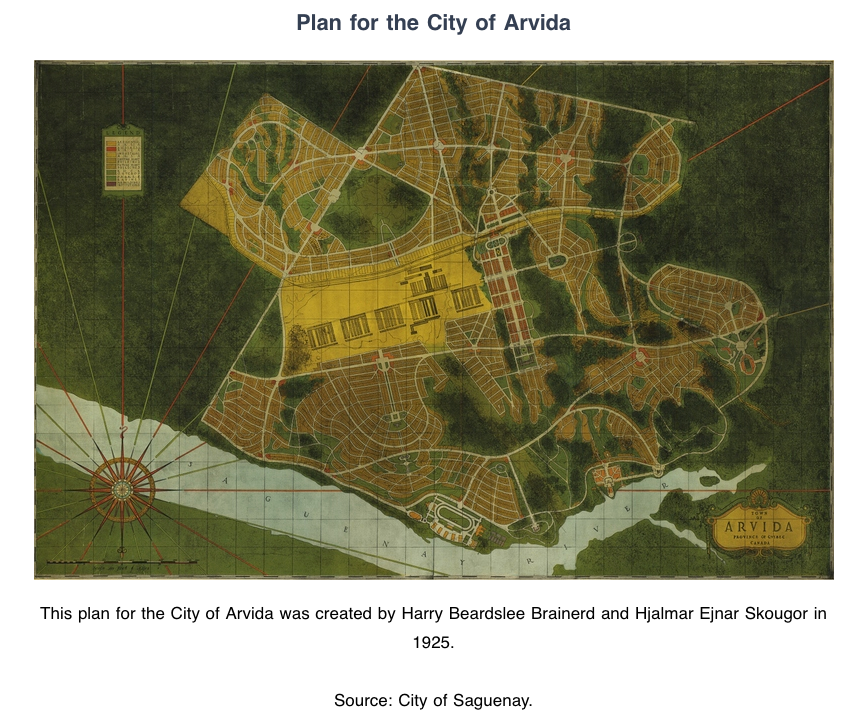

"Founded in 1926 as a community for employees of Canada’s first complex for aluminum production, Arvida is an outstanding example of a planned, single-industry town. Its name was derived from the first two letters of the three names of Arthur Vining Davis, president of the Aluminum Company of America. Architect H. B. Brainerd and engineer H. E. Skougor were commissioned to prepare plans for a city that would reflect the company’s standards of excellence."

"The urban plan constitutes an original synthesis of a variety of town planning theories and contemporary principles of urbanism, which earned Arvida an enviable reputation as a model city."

"The organic layout incorporates an ordered network of tree-lined streets enhanced by green spaces. Surrounding Oersted Park is the town’s original nucleus, known as 'The City Built in 135 Days', which speaks to the first of three construction phases extending from 1926 to 1950. The diversity of housing styles, some of which are successful examples of regionally inspired architecture, adds to the richness of the built environment. This well-preserved community illustrates the growth and importance of Canada’s aluminum industry during the 20th century."

"Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor was a Danish-born engineer who collaborated with architect Harry Beardslee Brainerd to create the original urban plan for the planned single-industry town of Arvida, Quebec. Commissioned by the Aluminum Company of America, Skougor and Brainerd designed the town in 1925 to reflect the company's standards, which led to a unique, ordered layout of tree-lined streets and green spaces. The town was founded in 1926 around the first aluminum production complex in Canada."

Additional information about the prior cross-national work of the Skougor/Brainerd partnership is provided by Culture et Communications Quebec, Digital Cultural Plan of Quebec, in the publication entitled Arvida, a planned industrial city:

"Harry Beardslee Brainerd and Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor"

"Originally from New York, Harry Beardslee Brainerd was educated at the Columbia University School of Architecture and subsequently specialized in various workshops where he trained in town planning."

"In 1924, Brainerd teams up with Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor, an industrial engineer specializing in house planning. Together, they create the plans of two new cities, Maria Elena in Chile, and Arvida. Commanded by Alcoa and drafted under the direction of its president, Arthur Vining Davis, Arvida’s plans are an original summary of urban planning, combining methods developed and tested both in America and Europe."

Hjalmar and Harry Brainslee Brainerd drew up the plan which the Alcoa Aluminum Company implemented to develop the city of Arvida in Saguenay, Quebec.

It was a city built by Alcoa in 125 days, described by the New York Times as a "model town for working families" on "a North Canada steppe".

Plan for the City of Arvida, Saguenay, Quebec, Canada

In-depth research and analysis of the socio-economic and political context of the Arvida project are provided by Professor Lucie K. Morisset of the University of Quebec in Montreal. She published her findings in Canada from Industry to Community: Arvida Factory Town, in the 2017 Bulletin of the International Committee for the Conservation of Industrial Heritage (TTICH).

"The model city, a veritable socio-industrial utopia, with its huge business centre, the 125 models of its 2,000 or so houses, and its community institutions, can teach us a great deal about various commonly neglected aspects of industrial heritage: housing, town planning, and working-class communities, and their interconnections with the history of planning and development."

"In North America, for example, but also in countries born of natural resource exploitation, from Scandinavian nations all the way to Australia, company towns, or in this case ‘frontier towns’ in the words of John Reps, have indeed established themselves in terms of a principle of settlement and a way of life."

"In Canada, home to a few hundred company towns, they have been a determining factor in the development of ideas and the imaginary with respect to territory, especially given that most of them came into being during the first half of the 20th century (as is the case for Arvida), when urban planning flourished and public authorities began to take an interest in housing and the creation of towns and cities. Experts estimate that the destiny of more than a million Canadians has been marked by company towns and they have furthermore re- iterated the extent to which, since the 1970s, ‘these towns [have] represented Canadian culture at its purest.'1"

"Arvida also prompts us to reflect on the ways in which we produce heritage, and on the social, economic, and cultural issues as regards its preservation and transmission."

"But Arvida, which has come down to us in a state of exceptional integrity and authenticity, also prompts us to reflect on possible transformations concerning the ways in which we produce heritage, and on the social, economic, and cultural issues as regards its preservation and transmission. Arvida serves as a contrast historically in the universe of planned industrial towns by way of an affirmation, from the very moment of its conception, of its being an ‘intentional monument’ (gewollter Denkmal), and the model town also distinguishes itself in the industrial-heritage field by having escaped decommissioning."

"As a company town, Arvida has served as a buttress for a liberal and democratic society and has featured a multiplicity of functions from its very earliest days. And while it is true that its plant was for a time under threat of abandonment, it has undergone a massive technological overhaul in recent years, an apparent guarantee of its sustainability."

"As opposed to what is found in most company and workers’ towns, where housing is rented and often remains the property of a single owner, Arvida’s houses were in fact destined, from the time they were built, to be purchased by local workers, irrespective of their ethnic origins or their social class. This component of social utopia, seminal in the sense of belonging of Arvidians and founded on personal fulfilment, has nevertheless resulted in a multitude of owners, an unusual complication when it comes to the conservation of planned industrial complexes."

"All things considered, it is not surprising that the much lauded initiative on the part of the municipality to protect, by way of regulation, 733 houses, in addition to several institutional ensembles, has earned it the Ordre des architectes du Québec award for its commitment to the quality of the built landscape or that the National Trust for Canada has also awarded the municipality and the residents of Arvida the Prince of Wales Prize for Municipal Heritage Leadership."

"Recognition will of course add to the corpus of scientific knowledge, but this pales in importance compared to what such acknowledgement means for Arvidians. For those who experienced firsthand or remember the network of multinationals that punctuated its history, the 3,000 soldiers who roamed its streets to protect the Allies’ aluminium (which changed the world, or so the story goes), the recognition of Arvida is above all a reconnecting with its history, with the global saga of the 20th century, memories of which Arvidians can lay rightful claim, above and beyond the administrative limits that erased them for a time."

"This is the industrial heritage that Arvidians, who fought to safeguard Arvida, protect and transmit, now calling for their community to be included on the Tentative List for World Heritage Sites in Canada. In ever increasing numbers, they are proudly restoring their home."

VII. Hjalmar's US-Mexico-Chile-Canada Connection

During the span of three decades, Hjalmar crossed the Atlantic from his birthplace Denmark, and accomplished extremely complex tasks in four countries in North and South America, using his mechanical engineering capabilities.

He traveled to New York by himself in his early twenties to start a career as a consulting engineer. Given his technological background and expertise, he sought out multinational companies with nascent industries focused on copper, coal, nitrates, and aluminum. He drew up plans to build immense steel structures to support their work, and kept abreast of newly emerging technologies. His work aimed at facilitating multimillion dollar efforts to embed themselves into complicated terrains in foreign countries, including the arrid and uninhabited Atacama desert in Chile.

To achieve these goals, he typically served as chief engineer charged with designing a broad array of extraction processes and manufacturing operations, construction of huge plants and warehouses, and core essentials of offices, housing, and community services, including stores, schools, hospitals, and churches.

What I admire the most is that Hjalmar preserved and expanded the egalitarian thrust of his values and goals throughout his career. They reached their pinnacle and were expanded in Quebec, Canada, the last of the four countries in which he worked. This strengthening was caused by a panoply of external factors and causes that he could not known about at the outset, most of which did not exist. He persevered to include them in his work even when they were not implemented by the corporations employing him.

As I described above, Hjalmar was especially concerned to find ways and means to reduce social-economic stratification by improving the working and living conditions of laborers. His also found ways and means to introduce into his work his broad interest in art, especially his view that aesthetics can and should be included amongs utilitarian considerations.

What is most remarkable is that his work found expression and a unique history-making application in a planned city named Arvida in Saguenay, Quebec. It was unique at the time, and remains a model to this day of what can be accomplished when there is collaboration by all the key players pursuing complimentary economic, social, and political goals. Such a scenario unfolded in the plan to develop the city of Arvida by the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa).

It is described as a "classless city" by Professor Lucie K. Morisset in Housing for the "Magic Metal" City: The Genesis of a Vernacular Home.

"The Sustainable Invention of a Spirit of Place"

"It is as though from Alcoa’s by now customary regionalism, combined with the utopian ambitions promoted by potential entrepreneurs of the site, surfaced the antithesis of the proletarian landscape of industrialized Quebec with its typical tenants and “quartiers des Anglais” (English neighbourhoods) reserved for the bosses, such as in Riverbend, Kénogami and Port-Alfred. This egalitarian achievement can be viewed as a kind of urban corollary to the popularization of aluminum itself after World War One, and of its international network."

"Rooted in the land and its specificities, it is no doubt among the factors that fostered the deeply rooted Arvidian identity still prevailing today. Besides contributing a typically Canadian habitat to the evolution of the American town as such, Arvida also historically marked the end of segregation along with that of tenement housing. Thus, even though Arvida is far from being the only industrial utopia, it was then and there that the industry and its need . . . pinnacle in its own right, Arvida appears to be the first and the last of its kind; in keeping with the promise of the 'magic metal of the 20th century,” it was the first to solve the workers’ housing issue by effecting a remarkable synthesis of all the schools of thought and experience that the company had gleaned from all over the world.""

"It is, no doubt, also the last of that monopolistic wave’s creations, and of that sort of company town, which even before Arvida was born, started to be gradually replaced by government initiatives and public housing programs. Finally, it remains unique, for only there, and only at that moment in the 20th century, was the precise conjuncture of company expertise and local practice able to produce this kind of Canadian aluminum habitat preserved to this day."

That Hjalmar Ejnar Skougor traversed four different countries to eventually play such a seminal role in the historic development of Arvida is to his everlasting credit. I hope his example inspires individuals around the world to imagine and implement similarly unique opportunities to advance human progress.

The painting of grandfather's home above conveys to me the vibrant warmth I feel when I think about his life -- and the many ways his accomplishments have inspired the lives of countless people, including mine.

He courageously ventured alone across the Atlantic when he was only 20 years of age. He arrived in New York City to start a career as a consulting engineer prior to being hired by any company.

In three short decades, he performed work in companies in four different countries in North and South America, creating new communities and implanting industries where none had existed before.

The violinist painting above hung in his home and later our home to inspire me when I was learning how to play the piano.

What strikes me is Hjalmar's audaciousness. He publicly criticized the Mayor of New York and Board of Estimates, in a New York Times open letter for not producing a workable strategy for developing ports along the Hudson River!

His candor and outspokenness reminds me of similar tendencies I have expressed in my work as a political scientist. What might have influenced me the most was the egalitarian thrust of his ideas. While working for large corporations, he inserted ways and means for improving the living and working conditions of laborers in North and South American countries, and reducing class differences and social stratification.

He was undaunted when his efforts did not bear fruit, but persevered until he was engaged to contribute to a corporate plan to build an entire city -- with housing and community development opportunities that put all members on an equal footing.

What I hope in these challenging times is that people whose lives are uprooted will be inspired by Hjalmar's examples of what one individual can accomplish.

Doing so may require bold ideas and endeavors without official endorsement or support at the outset. We need new ways of doing things that can be instigated from the ground up, by regular people seeking to use their own ideas to overcome threats to their lives and livelihoods.

In my case, as a citizen of Switzerland, I decided to build a network to globalize the self-governing principles and practices of Switzerland's direct democracy form of government, which was pioneered centuries ago by Alpine dwellers.

The network is designed to show voters around the world how to use direct democracy practices used by Swiss citizens throughout the year to mandate enactment of their priorities responding to their needs, such as initiatives and referendums.

Time will tell whether it succeeds. Following in my grandfather's footsteps, the most important thing is to have big ideas and do everything possible to get them into action!

As the famous 19th century Danish author Hans Christian Andersen wrote:

"Nothing is too high for a man to reach, but he must climb with care and confidence."

Sources

Culture et Communications Quebec, Digital Cultural Plan of Quebec.

Arvida: A Planned Industrial City.

Espejo-Leupin, Patricio.

Edgar Stanley Freed, los Guggenheim y la industria del salitre. Pampa Negra Ed. 2021.

Translation: Edgar Stanley Freed, the Guggenheims and the saltpeter industry.

Espejo-Leupin, Patricio.

El ingeniero danés Hjalmar Skougor y la oficina salitrera María Elena. Una historia de diseño industrial y arquitectura en la pampa chilena bajo el "Sistema Guggenheim"-Espejo- Taltalia16.

Translation: The Danish Engineer Hjalmar Skougor and the "Maria Elena" Nitrate Work. A History of the Industrial Design and Architecture in the Chilean Pampa under the "Guggenheim System".

Galaz-Mandakovic, Damir and Francisco Rivera.

Revolution and Resistance in the Desert: The Guggenheim System's Impact on Nitrate Mining and Society in Atacama, 1926–31.

Johns Hopkins University Press. Volume 65, Number 2, April 2024.

Google Arts and Culture/UNESCO World Heritage.

Humberstone and Santa Laura Saltpeter Works, Chile: Rescuing heritage on the Chilean Pampas

Government of Canada.

Arvida National Historic Site of Canada

Lucie K. Morisset.

Conférence, les maisons d'Arvida par la professeure Lucie K. Morisset

Morisset, Lucie K.

Housing for the "Magic Metal" City: The Genesis of a Vernacular Home.

Morisset, Lucie K.

Les villes industrielles planifiées et le patrimoine industriel en contexte de désindustrialisation.

Glaser-Schmidt, Elisabeth.

The Guggenheims and the Coming of the

Great Depression

German Historical Institute, Washington, DC.

Business and Economic History, Volume twenty-four,no. 1. Fall 1995.

Copyright¸1995 by the BusinessHistoryConference. ISSN 0849-682.

New York Times

Sidewalk Shuttle May Get a Tryout

December 1, 1918.

Skougor, Hjalmar Ejnar.

Rosita, Mexico, a Carefully Planned City: Pleasing. Confortable and Hygienic. (See Coal Age, Vol. 19, No. 22 (June 2, 1921): 983–987, and Coal Age, Vol. 19, No. 23 (June 9, 1921), 1037–1040.)

Skougor, Hjalmar Ejnar.

Censures Estimate Board: Engineer resents attack.

New York Times, April 25, 1920.

info@hjalmar-ejnar-skougor.com

Copyright © 2025

All Rights Reserved